Our journey to Cape Wrath

Ken Taylor/Cameron

cameron@twinoaks.org 1 December 2018

updated 28 March 2019 with more photos from our trips, kindly provided by Campbell’s daughter Sally Semple

Loch Lomond and beyond

photo: Michael Macgregor

“Loch Lomond from the Dumpling”

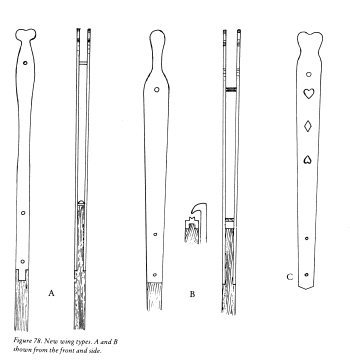

We left from the Scottish Hostelers’ Canoe Club boathouse at Auchendennan Youth Hostel on the west shore of the Loch, near its south end. [In those days (and sometimes still) kayaks were known as canoes in Britain.] That was where we’d done our first kayaking in the Percy Blandford PBK 18 that we had built in Campbell’s family’s garden in the west end of Glasgow, on weekend trips with the Club when we all camped on one or other of the several islands in the Loch. At least once I remember Jack Henderson being with us. He was quite the hero, of course, as not only was he an Olympic kayak racing competitor but he and Eric Simpson were the first two people to ever kayak around Cape Wrath — the northwest tip of Scotland, renowned and feared for its notorious tide rip. Two other members of the Club had by that time (the early 1950s) also been around the Cape — Hamish Gow and Alasdair (if I’ve got his name right). I don’t remember now when it was that Campbell and I first began to think of rounding the Cape ourselves.

photo: Colin Wheatley

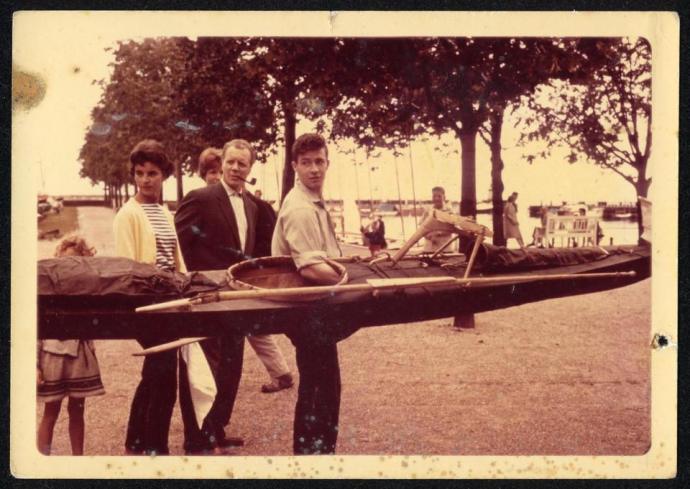

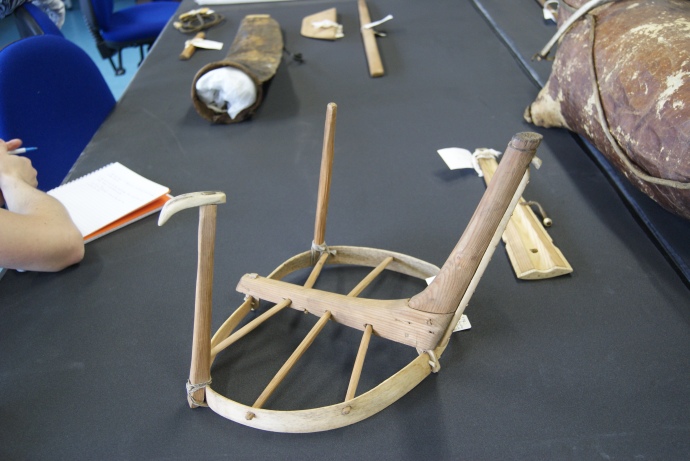

Our first real trip was, just the two of us, using our PBK 18, up the Loch to Tarbet and a one and a half mile portage using our “bogies” (folding metal frames with pram wheels, small enough to go inside the kayaks, which we learned about from the SHCC members) to Arrochar, down Loch Long to Loch Goil and the Holy Loch, and back the same way.

photo: J. Campbell Semple

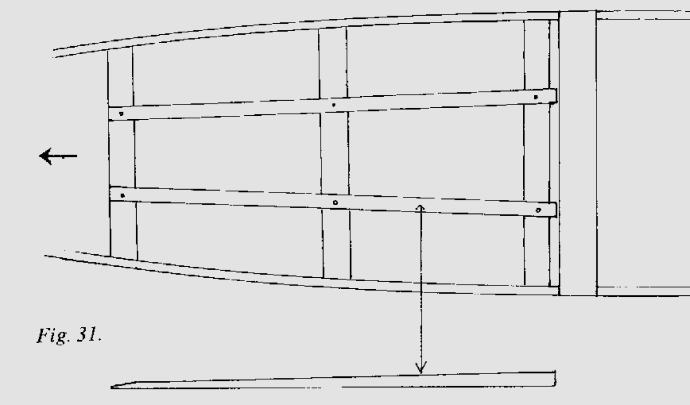

One to show how we used the “bogies” — and the kind of rudders that we had back then.

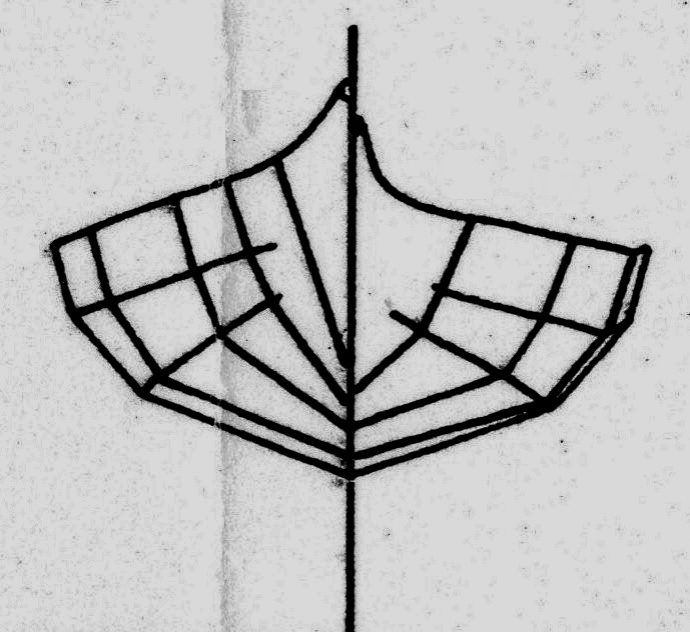

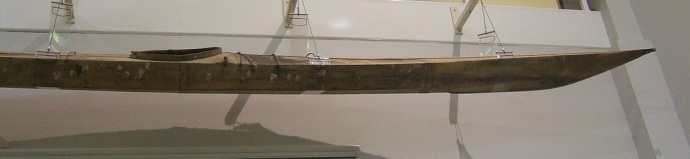

It went well enough, and since it was later in the year than we ever went again on that trip we were able to catch more mackerel than we could eat, which was nice, but we immediately found that using a double simply didn’t work for us. We were young and argumentative and we spent every mile of every day of the trip arguing about the course chosen by whichever one of us was in the rear and controlling the rudder. When we got home to Glasgow, without even one word of discussion (at least that’s how I remember it), we immediately began building two singles! For these we simply scaled down the PBK design to about 15 feet, sharpened the bow cross section somewhat, and ended up with extremely serviceable single kayaks that did us proud for many years. Mine was the “Scottish kayak” I took with me to Greenland in 1959. Later, after I’d left for the US, I sold it for a few pounds to a new member of the Club, and forgot about it. It was a wonderful surprise for me, many years later, when I recognized it as the second kayak seen at the beginning of the film of Hamish and Anne Gow’s amazing 1965 trip to St Kilda — the one that never did make that trip as, sadly, it’s owner turned back after a few miles.

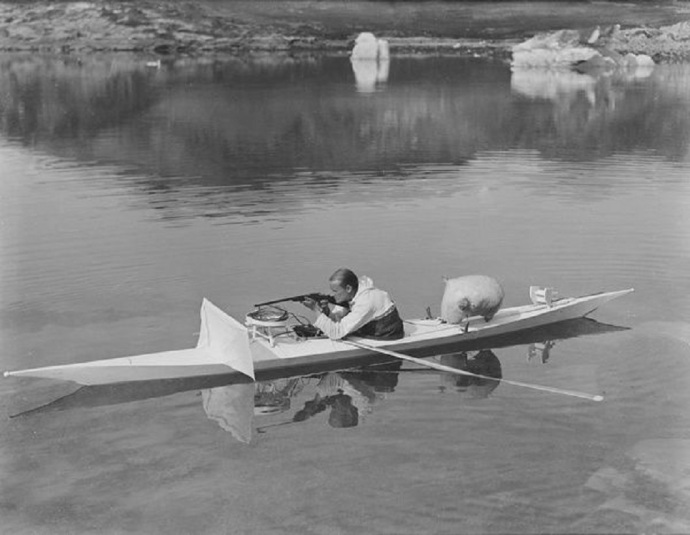

Here it is, in 1958, at Kinlochbervie —

photo: Harald I. Drever

So it was in these two kayaks that we did all our trips from then on including, of course, the eventual rounding of Cape Wrath. We built them with marine quality plywood for the frames and mahogany (believe it or not) that we got at a very cheap price from a lumber yard owned by the father of a boy in the Boy Scout troop we belonged to (the First Glasgow “B” Troop), using only brass screws. Regular canvas stretched over the hulls with the help of Campbell’s father who was an artist, two or more coats of oil paint. And they always seemed able to do even more than we ever asked them to.

Our second trip began by paddling down to the bottom of the Loch and, by way of the quite small River Leven to the estuary of the River Clyde, at Dumbarton. That, of course, was a new and a very different thing altogether — with ocean liners and freighters making their way up river to the docks at Glasgow. At one point the nerve-wracking experience of having to choose between heading across in front of a gigantic seeming passenger liner or waiting for it to go by us first (I seem to remember that we crossed in front of it, safely) as our plan was to more or less immediately head across the estuary, aiming for the area of Greenock and Gourock and spend our first night somewhere over there. Which we did, uneventfully, a few miles east of Greenock and then went on the next day, past Gourock and around the headland and into the increasingly open expanse of the Firth itself. The plan was first to head west and paddle through the Kyles of Bute, which would be quite sheltered water. We stuck to the coastline as far as Wemyss Bay and made the two and a half mile crossing to the west side of the Firth and around Toward Point into the Kyles of Bute. This was a gentle, scenic beginning to the trip.

photo: Elliott Simpson

We camped somewhere on Bute and then came down to Ardlamont Point between the Kyles and the bottom of Long Fyne. This was where we had to decide on whether or not to head south the seven and a half miles to the Isle of Arran, somewhere we had both been before on family vacations. But there was a strong wind that day from the south and we immediately knew that we could forget about Arran. It was also raining off and on and we took shelter in an open boathouse, cooked a meal and waited for hours to see what the weather would do. In the end we spent the night there and finally, just at dawn, we decided the wind had slackened enough that we could safely go around the Point and into Loch Fyne. A few miles up the shoreline we landed in front of Ardlamont House and camped under a group of pine trees with the pleasant sound of the wind in their branches something I remember to this day. We’d hardly slept, it had been hard going, and we were exhausted, so we thoroughly enjoyed catching up on our sleep and doing nothing at all all day.

Next we made our way up the east shore of Loch Fyne, past Portavadie, eventually crossing to the west shore as we were heading for Ardrishaig and Lochgilphead and the Crinan Canal. We planned to go through the canal thus avoiding the 80 mile trip around the Kintyre peninsula, and the possibility of wild weather (and “notoriously strong currents”) at the exposed Mull of Kintyre. Of course we’d never gone through a canal in our kayaks before this so it was going to be a bit of an adventure in itself. Built between 1794 and 1801 and gone through by Queen Victoria in 1847 it had long been, and still was, a very popular short cut to the Inner Hebrides area of the west coast for both commercial and pleasure boats of all kinds. It has 15 locks and is about nine miles long.

photo: J. Campbell Semple

Campbell’s kayak on its bogie when we reached the first lock of the canal

What I remember of it is the experience of sitting in our kayaks along with a few full size boats in a low water level “basin” while the water level rose in a strange and slightly scary way … until the lock ahead of us could be opened and we could all move ahead a mile or a few miles to the next lock. A unique experience but fun in its own way and it all went well without any particular problems for us in our “tiny” boats!

photo: scottishcanals.co.uk

photo: Clyde Cruising Club

Back to the sea at Crinan in a stretch of water well sheltered by the island of Jura, with Scarba, our next destination just a few miles to the north. Between the two is the famous Corryvreckan whirlpool that we’d heard about and read about all our lives. We’d been told by Hamish and Alasdair that it was passable at slack tide and we were there to check that out. It turned out to be safe enough — just weird and nerve-wracking with the water surging up from below and shifting our kayaks to one side or the other, quite out of our own control. But fascinating, well worth a visit, we were glad we did it.

photo: Bizarre Beauty

We continued north, inland of a succession of small islands, camping on Shuna. Next day we passed Loch Melfort to the east and Luing on the west, heading for the famous old “Atlantic Bridge,” also known as the Clachan Bridge. This fine old structure has connected the island of Seil to the mainland since 1792. Slate (as roofing material) was quarried there and on neighbouring islands until the 1960s. We paddled under the bridge and on to Oban in quiet water on a beautiful day.

photo: visitscotland.com

It was just another 10 miles or so to Oban where we caught a train home to Glasgow. In those days the “luggage vans” on Scottish trains were much larger than nowadays. In fact, we were always able to wheel our kayaks on their bogies into the vans, with room to spare.

That was our first “real” trip on our way to Cape Wrath (Loch Long, etc., the previous summer had felt more like a training run). Uneventful really, though going through the Crinan Canal and paddling over the waters of the Corryvreckan had certainly been new and different experiences for us. It definitely felt like a good start.

– x – x –

The following year was our first major trip — Oban to Mallaig rounding Ardnamurchan Point on the way. It was 1955, a year when the weather in June couldn’t have been better. By that time we’d learned that the earlier in the summer the better, before the rains began in earnest. Also, being out on the coast and going around most of the peninsulas we came to we were “out in the Atlantic” as we used to put it. I vividly remember the many days when we would look in to the mainland and see the rains pouring down on the mountains while we were enjoying blue skies and brilliant sunshine.

First the train ride to Oban which, with Mallaig, was one of the two railheads on the west coast in those days. It was a day trip of several hours so when we got to Oban and got our kayaks down to the harbour and loaded up and ready all we had time and energy for was to paddle out to and around the far side of the island of Kerrera — which completely encloses and shelters the bay and harbour of Oban. And there we had our first night’s camp. We used an Army surplus “pup tent” just big enough for two to sleep in tho’ we did also have a smaller, lighter weight tent which we used at times as our “kitchen,” pantry. etc. In fact, that year, as often as not we were able to light outdoor fires to cook on. In those days the appropriate maps were the old “inch to the mile” Ordnance Survey ones which gave enough detail that we used to could, quite successfully, pick out our campsites ahead of time.

The next day was up the Sound of Mull the 30 miles to Tobermory where we stopped in for fresh milk and a bar each of fruit and nut milk chocolate — the granola bars of those days. Then across the mouth of Loch Sunart to camp on the near side of Ardnamurchan. In the process we paddled at a distance of maybe three miles past “Drumbuidhe,” on the mainland where, many years later, Campbell and family had a wonderful vacation home in what had once been a “tacksman’s” house, with its barns, sheds, etc., where Campbell installed a Darrieus windmill, a mini-hydro power unit , and a solar panel array. The pride and joy of his later years and a place that I thoroughly enjoyed visiting two or three times more or less recently.

photo: J. Campbell Semple

Next was along the shores of Ardnamurchan to the lighthouse on the point where we camped for a few days. The weather was calm, no problem at all, but that was special since (as many people don’t realize) Ardnamurchan Point is actually the westernmost point of mainland Britain — farther west than Land’s End. Of course we visited the lighthouse and enjoyed meeting the “keeper’s” family and being shown the marvels of the light. They told us that there was a large sheep farm just a few miles inland where we could probably get some fresh milk, and where the farmer was about to begin the annual shearing of his sheep.

I remember that we took a swim in the sea to mark the occasion — never again, that water was cold like I at least had never imagined.

So the next day we walked in to the sheep farm, got our milk, and “signed on” so to speak to help out the next day when the shearing would begin. The farmer’s family were from Ayrshire and were running an unusually large number of sheep for that part of the country. Other farmers and crofters from miles around would be there to help with the work involved. Early the next day we enthusiastically joined the crowd of helpers. We got the job of dragging individual sheep one by one over to the shearers. It was 1955, so did they do the job with hand clippers or electrical? I wish I could remember. We all worked for a while and were then called into the farm kitchen (in shifts, there were so many people) for an enormous breakfast which I remember really surprised us it was so generous. And we all worked all day. The lighthouse keeper, who had been a professional carpenter, was there too with the very specific job of sawing off part of one of the horns of a ram which had begun to grow “inward” and become a problem. He got a lot of leg pulling about that but, hey, he was the right man for the job. It was a two day job and, as far as we were concerned, it was just a lot of fun. So we were quite surprised as we were leaving after it was all over when the farmer walked a way with us, thanking us for our help, and then pulled out the biggest roll of bank notes that I had ever seen and wanted to pay us for our work. Well, of course, we thanked him and refused to accept any money for the fun we had had (later we calculated that the amount he had been offering us would have more than paid for the entire cost of our trip).

A young man who was working for the summer for the Fish and Game government agency, and also romancing one of the farmer’s daughters, walked us back to our camp at the lighthouse as he was interested in finding where a certain fox was living. Apparently it was part of his job to find it and kill it if he could. We enjoyed his company, had a pleasant walk back to our camp and, as we got there — the most amazing sight. It was just at sunset and a haar (sea fog) had covered the entire area of sea visible from where we were. In the light of the setting sun it was vividly pink in colour. And sticking up out of it were several islands — Muck, Eigg, Rhum, and some others. It was beautiful. Mind-blowing.

Here’s very much the same view in different weather conditions.

photo: Michael Macgregor

“Eigg, Rum and Skye from Roshven”

So then and there, we decided — something we had not really planned to do — we had to go out to those islands. The next morning we left, in beautiful weather, for the closest island, Muck (OK, OK, old joke: the islands used to be called “the cocktail islands”), planning to have a “drum-up” (do people still use that expression for a tea break?) there, and then cross to Eigg where we would camp.

On the way to Muck something very special. In those days many people still used to argue about whether or not a basking shark had strong enough tail muscles to breach. We were about half way across the seven and a half mile stretch to the island when we heard this tremendous noise off to our right. Looked over and there was a basking shark in mid-air. Did you just see that? we asked each other and … it did it again. [I’ve since read in Gavin Maxwell’s “Harpoon at a Venture” that indeed they can.]

Three miles farther to Eigg where we landed at the southern end, asked for where to buy some milk and were directed to the store — at the top of the track in the centre of the island. As we walked in two small girls were chatting and ordering things from the woman store keeper. They turned and saw us, two total strangers, and in a flash dropped their English and switched to Gaelic! We bought the usual, enjoyed the wonderful view all around, returned to our kayaks, and paddled around to the north side of the island to make camp. And from there we had a fine view of Rhum, some six miles across the Sound.

Eigg, when we were there, will still have been in the ownership of the Runciman family, before the disastrous succession of short-term owners did their damage. A great account of how the islanders finally gained ownership and control of their island and its affairs can be found at: “http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/sep/26/this-island-is-not-for-sale-how-eigg-fought-back.” Among much else, the islanders are rightly proud of having created “the worlds first fully renewably powered electricity grid.”

Rhum, which was purchased by the Nature Conservancy Council in 1957, was still a privately owned sporting estate when we visited. Someone had advised us to check in with the staff at Kinloch, which we did and were told that we were welcome to camp anywhere in the bay. Apparently (as I was told when I visited there, by mail boat, in the 1980s) the island is notorious for its insect population. Unfortunately, we hadn’t known this in 1955 and we spent an absolutely miserable night in our old-fashioned tent being eaten alive by clegs and midges. Our breakfast the next morning we simply had to interrupt in order to flee out to sea in our kayaks, leaving the insects and the island behind.

Our next stop was the small island of Soay, ten miles away, close in under the famous Cuillin mountains of Skye. Campbell, who somehow or other knew that Tex Geddes who had been the principal harpoon operator of Gavin Maxwell’s ill-fated shark fishing operation of just a few years before was now living there with his family, was keen for us to drop in on them to visit and meet this remarkable person. Myself, I honestly don’t have any clear memories of our visit but Campbell speaks of it in his podcast recorded by Simon Willis.

photo: J. Campbell Semple

Tex Geddes at Soay. In 1960 he published his own account of those days, “Hebridean Sharker.”

After a few days on Soay with the Geddes family we headed due west to Elgol on the Strathaird peninsula of Skye itself for the usual milk and chocolate and lunch on the shore. And from there, via the much larger peninsula of Sleat, on to Mallaig where we could catch a train home to Glasgow.

A fine trip. We both agreed that it had been “the real thing” and unforgettable also for the sunburn which had been our only real problem!

– x – x –

The next two summers we took jobs on a construction site so it wasn’t until 1958 that we were back on the coast. We began, of course, at Mallaig, heading north up the Sound of Sleat, past the mouths of Loch Nevis and then Loch Hourn. Just north of the latter we camped on a promontory at Sandaig, looking inland a mile or two to the small house that later became known as Camusfearna. So, just three years after having visited Tex Geddes on Soay, now we were camped for a night within sight of the house where Gavin Maxwell, exactly then, was writing his wonderful “Ring of Bright Water.” We didn’t know that at the time, of course, and we saw no sign of him. I’ve often wondered if he was there when we were and maybe noticed our tent where we camped on that tiny spit of land with our kayaks many feet below us at the water’s edge.

The view from our campsite at Sandaig, a part of the “ring of bright water” of Kathleen Raine’s poem The Ring. Campbell making breakfast outside our second tent.

On then through the narrows of Kyle Rhea, after a stop at Glenelg, through Loch Alsh and out to the open sea, through where the dreadful Skye Bridge had yet to be built, to the Crowlin Islands where we camped on Eilean Mor. This was one of the several uninhabited islands we camped on which certainly helped keep us out of trouble but in fact we never once were bothered by any landowners. In those days “access” had not yet become an issue. Another unique feature of our trips in those years was that never once did we ever come across any other kayakers, anywhere, not even once. Not that we expected to as back then our SHCC and a club on the River Tay, so far as any of us knew, were the only two groups of sea kayakers in the whole of Scotland.

Then north, staying to the east of Raasay, and in to camp in the outer part of beautiful Loch Torridon.

I think it must have been on that stretch of coast that we had the fascinating experience of paddling among enormous swells coming in from the west. They were of the size that, if we’d been paddling across them and not parallel to them we would have had to paddle uphill to their crests and then downhill to the next trough. Since we were going parallel to them it meant that most of the time we were out of sight of each other and only now and again did we see the other kayak when we both happened to be up on a crest at the same time. It was kind of fun.

The next day up the coast to Gairloch where, I think it had been recommended to us by someone, we put the kayaks on their bogies and portaged most of the the six miles to Poolewe.

But here we took a detour and turned inland to spend two or three days on Loch Maree. Campbell was very keen that we do so maybe because it is, apparently, often referred to as the most beautiful loch in the Highlands. Whatever the reasons we were both delighted that we did. Not quite as long as our familiar Loch Lomond it also has a good many islands. And, of course, it was on one of these that we camped for two days. The weather was fine and we enjoyed a relaxing time there in much calmer conditions than on the coast.

photo: Pinterest

photo: J. Campbell Semple

At one of the islands on Loch Maree. Our “bogies” on the after decks as we would be using them again as soon as we left the loch.

Then back to the road for the short distance to Poolewe and soon we were paddling past the palm trees of the extraordinary Inverewe Garden already by that time in the care of the National Trust. Through Loch Ewe and, if I remember rightly, we went around Greenstone Point so never in fact close to the notorious Gruinard Island, off limits until 1990 because of World War Two anthrax experiments conducted there.

That brought us to the Summer Isles and in a persistent drizzle we passed Priest Island and on to Tanera Mor where we planned to camp. This is the island where Frank Fraser Darling and his wife Bobbie spent three and a half years back in the 1940s working to establish a functioning farm. We had read his “Island Farm” about that project and others of his books and greatly admired his work as a naturalist. It was kind of in honour of him that we went there and camped for a night. But in dreary, wet weather so there was no great pleasure in it, just something we had wanted to do and did. Next day to little Achiltibuie where we took another break from the actual kayaking and went for the day to Stac Pollaidh (it was still called Stac Polly in those days) a quite remarkable little mountain. At only just over 2,000 feet it’s “not even” a Munro, but it has its own quite distinctive shape and being so close to the coast the views from its summit are superb.

photo: Tripadvisor.com

Stac Pollaidh from the south so those are the waters of an inland loch, not of the sea.

Near the foot of the mountain an attractive little sandy-haired Cairn Terrier attached itself to us and seemed to want to go wherever we did. We guessed that its people must be somewhere up the trail so let it come with us. Which it did, all the way to the summit. It was a beautiful day with good visibility and the views were amazing. Especially we were impressed to be able to see, looking up the coast to the north, the next few days of our kayaking laid out like a map, but real. Maybe the only place on the entire west coast where that’s possible.

photo: anon

Admiring the view from the summit. Looking back at Tanera Mor perhaps?

Eventually the dog went off with someone else and we headed back down and back to wherever it was we’d left the kayaks and camped on the shore of Enard Bay, crossing the next day to Lochinver, the biggest place we’d seen for a long time.

Perhaps because it was a well-known name and place we made sure to go round the Point of Stoer.

That’s Campbell on our way up the side of the peninsula, with the Old Man of Stoer visible in the distance.

photo: J. Campbell Semple

And a shot of me as we passed close to the “Old Man.”

So — around the Point and on to a campsite on the south side of Eddrachillis Bay. Here the weather turned foul and we spent the day in our tent reading books and playing chess until in the evening it went calm and we decided to cross the Bay even though it was the “almost dark” of night time that far north in the month of June. I think it was here that we had an absolutely comical scramble to get our kayaks over the seaweed covered rocks, chasing the receding water, as the tide went out as fast as we’d ever seen. But was it ever worth that struggle! Almost as soon as we got going across the Bay the water became phosphorescent and every paddle stroke, every movement of the kayaks, was lit up by this beautiful, extraordinary flickering of light. The only time we ever saw that. It was wonderful, unforgettable.

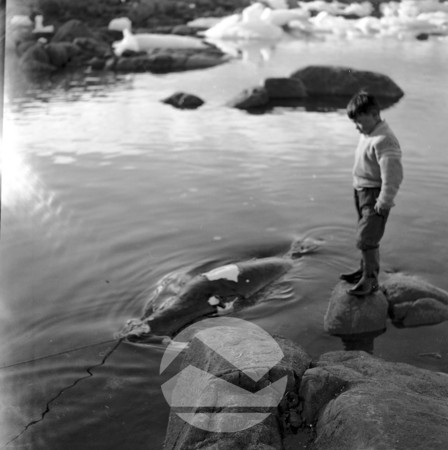

We stopped in at Scourie and then hiked along the shore, actually the cliff-top, until we were opposite Handa Island where we lay on the grass for a long, long time watching the hundreds and thousands of birds that nest on the cliffs. Each summer, supposedly, nearly 100,000 seabirds breed here, including internationally important numbers of guillemots, razorbills and great skuas. Not to mention the puffins! What a sight!

photo: http://www.danheller.com

Speaking of puffins, from time to time we would come upon an large group of puffins out in the water. Always a pleasure to see them, because of their extraordinary beaks. As we came up on them (silently, of course, so totally surprising them) they would try to fly to get away from us. But they were full of fish and too heavy to take off so after a few vain attempts they would give up and simply dive and easily get away from us that way. There were often cormorants (“shags” really) and occasionally a place with lots of gannets. They were my favourites as their way of diving from a great height to catch their fish was so impressive. For some reason I always saw that maneuver as if they turned on their backs just before entering the water but I’ve since seen videos of them doing it and no, they just fold their wings tight at the last moment. And then it would be several moments before they re-surfaced in “sitting on the water” posture, shake themselves to dry off a bit and — eat their fish.

By now we were just seven and a half miles from Kinlochbervie which was to be our last port of call before rounding Cape Wrath. We went first to the village itself for the usual supplies. That was where we met Dr. Harald I. Drever.

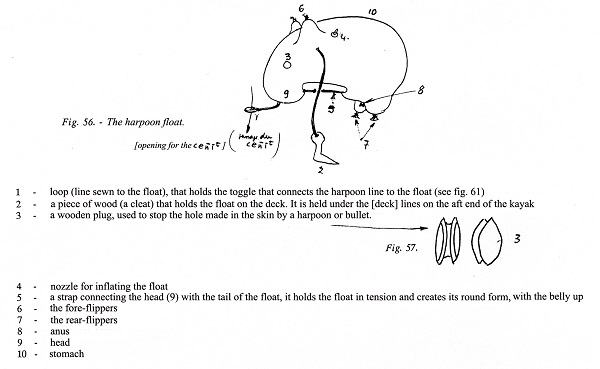

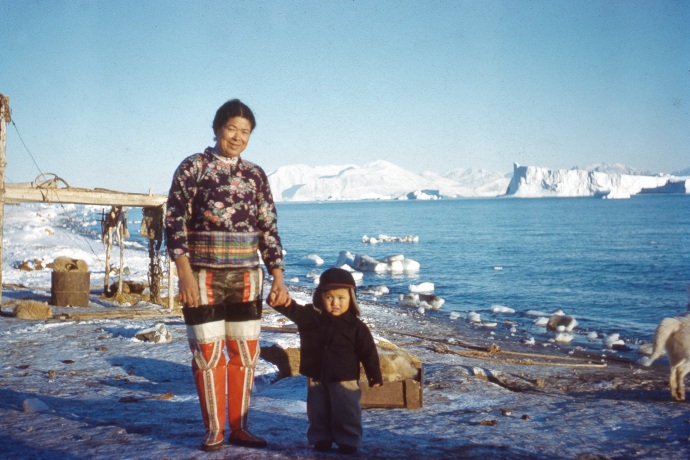

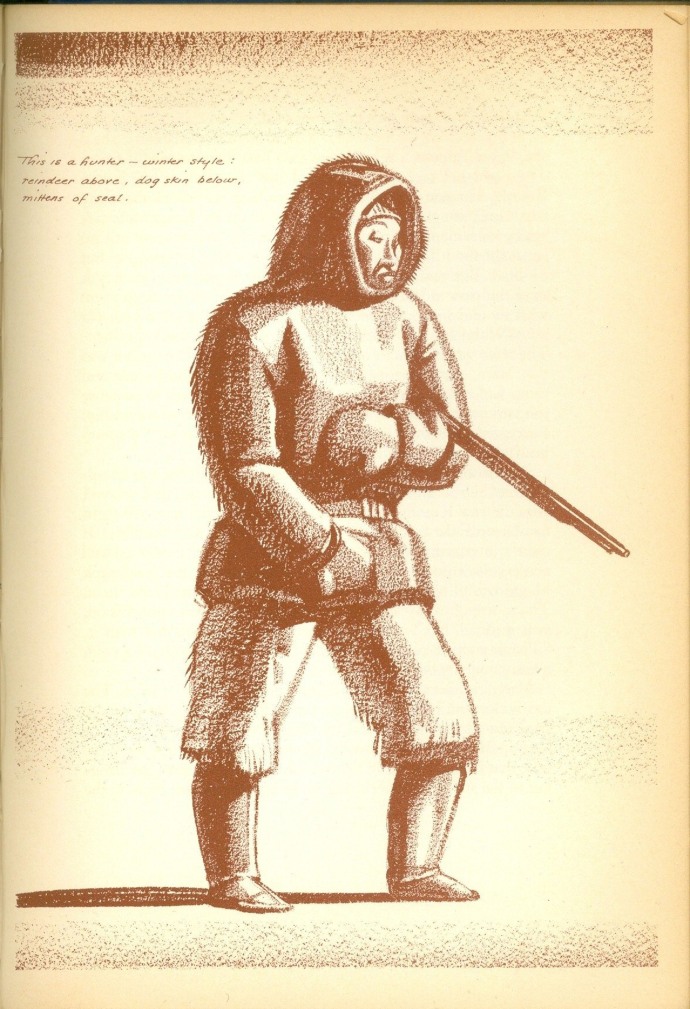

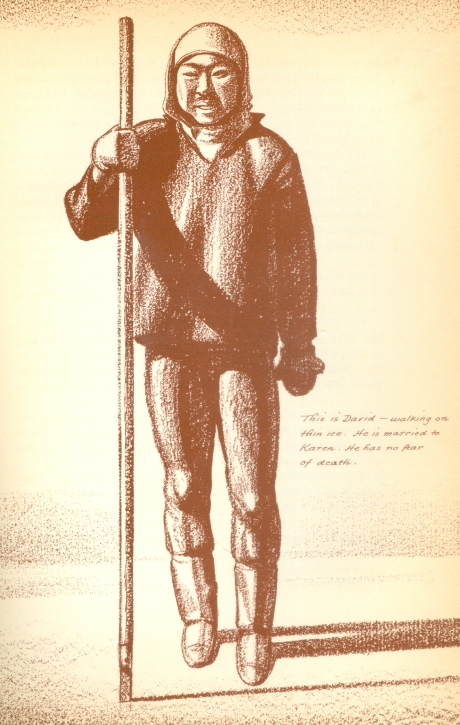

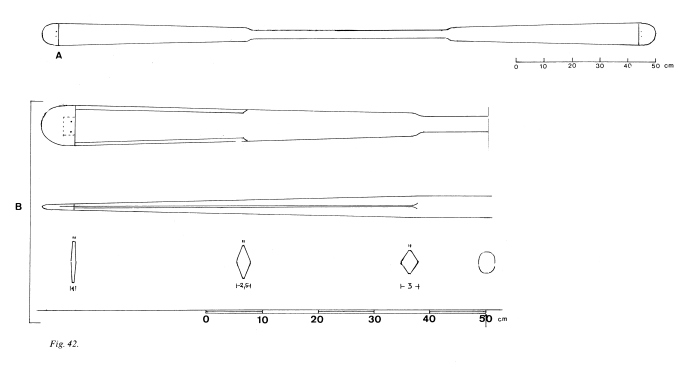

He came down to offer any help we might need and to admire our kayaks. And, when asked politely about his interest in our kayaks, told us of his time in Greenland, as a geologist, staying at Illorsuit an Inuit village where the men still hunted seal by kayak. Well, needless to say, that was very special indeed from our point of view.

We went up the coast a mile or two to camp, as we already had in many places, on the machair. In those days this was, legally, of free access to the public. And we arranged for Drever to come visit us there the next day to try out one of our kayaks. Which he did with no problems though protesting that it had been many years since he’d ever been in a kayak. He invited us up to the hotel for drinks after dinner when we enjoyed talking in more detail about his times with the Inuit.

The next day was the big day.

On the way to the Cape we took a look at Sandwood Bay but the surf seemed a bit too much for us so we just kept going. A bit farther north we met up with a group of four or five local men out tending their lobster pots in what looked to me like the biggest rowing boat I’d ever seen. We chatted for a while and they warned us that there was the remains of a northeast storm still running on the coastline around the Cape. They advised us to wait for the tide to turn as it was actually against us at that point. We were able to go ashore in Keisgaig Cove to rest for a while, make tea on a driftwood fire.

When we continued and finally reached the Cape, now being being carried on by the tide, it was worse than anything we’d ever imagined. The wildest water we’d ever seen, broken up into short waves and heaving, vertically thrusting, sinking volumes of water without rhyme or reason, there’s no other word for it — it was terrifying. But we had to go through it, the tide was carrying us through it, there was no turning back. Campbell stayed fairly close in to shore while I went quite a bit farther out hoping (vainly) that it might be less wild out there. We lost sight of each other … later Campbell told me that he had actually turned back at one point to look for me, surely the bravest thing that anyone I knew had ever done! He describes the insanity of it all in his article published in the Glasgow Herald of October 25, 1958.

Eventually we were past the Cape itself and took shelter behind a small islet while we looked out with dismay at the huge waves bearing down on us from the northeast, just as those fishermen had warned. We actually wondered and discussed if we and our kayaks could handle waves that huge. They seemed to be well over six feet high and the tide was still sweeping us irresistibly along and into their clutches. The wind itself was not too bad, but the waves … well, that was when we learned that the kayaks could handle more than we had ever asked them to before.

There is a possible landing just around the Cape but neither there nor at Kearvaig, four plus miles along the coast, would the surf have let us land. There was nothing for it but to continue the 13 miles or so to the shelter of Faraid Head, with Durness just across the base of that peninsula. Which we did and finally were able to land on a beautiful and beautifully sheltered beach — thoroughly exhausted and (no exaggeration) lucky to be alive.

photo: Travel Scotland

We had some more tea to help ourselves warm up and calm down, got the kayaks on their bogies and headed for the local Youth Hostel. Hot baths and a good meal and we felt a lot better and … following Jack, Eric, Hamish and Alasdair, we had done it, we had gone around Cape Wrath.

The next day came the “price you have to pay” part. To get back home to Glasgow we needed to return to Kinlochbervie and hitch a ride on a fish lorry to the south. And Kinlochbervie was 18 miles from Durness! But it was, obviously, just part of the plan. So, with the kayaks already up on their bogies, a quick breakfast, and we set out. It happened to be a Sunday. Still in the streets of Durness the Englishman, a fisherman, with the motor bike and sidecar who we had met when we camped on the machair outside Kinlochbervie showed up. “What are you fellows doing?” “What are you doing?” “Well, I can’t fish, in this heathen country, ‘cos it’s a Sunday!”

A few minutes later and we had accepted his offer of a tow to where we were going and with one of us facing backwards in his side car and the two kayaks on their invaluable bogies attached behind him we were off! Surely the last thing we had ever expected! But it worked. I don’t remember what was the slow speed he needed to drive at, but it worked.

photo: J. Campbell Semple

As the photo shows he brought his baby child along — something that I had completely forgotten.

When we reached the head of little Loch Inchard, some four miles shy of Kinlochbervie, we said we could do it by kayak from there and he dropped us off. Let me say it again: “we don’t know how to thank you enough!”

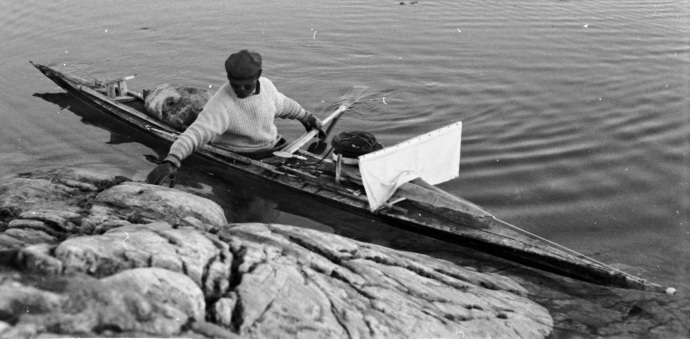

photo: J. Campbell Semple

Somewhere off the northwest coast. Just a photo that evokes it all for me.

And so we were back at Kinlochbervie, ready to try to persuade some lorry driver to give us the ride we needed. BUT the weather had turned foul and the fishing boats were all riding it out, out at sea! And the lorries were sitting idle in the village waiting for the boats to come in and unload their fish. That meant three, it may even have been four, days stuck in Kinlochbervie. But, of course, it also meant that many times of Dr. Drever having us up to the hotel again for “drinks after dinner.” And plenty of opportunity to ask him all we wanted to about the kayak hunting lives of those Inuit he had met in northwest Greenland.

In due course, with our kayaks securely lashed down on top of a huge load of fish boxes we got our ride south — but to Edinburgh. No problem, a short train ride through to Glasgow and we were home.

And then, a few months later, the unforgettable letter from Drever inviting me to go spend the summer of 1959 in Illorsuit.

– x – x –