KAYAK HUNTING IN ILLORSUIT

GREENLAND

1959

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Hunting Trip to Umiamako

Chapter One Life in Illorsuit; Chapter Two Subsistence activities; Chapter Three Ikerasak Village and Uummannaq Town; Chapter Four Building the Kayaks; Chapter Five Variations in Kayak Design; Chapter Six: Skinning the Kayaks; Chapter Seven The Hunting Equipment; Chapter Eight The Hunting Trip to Umiamako; Chapter Nine The Kayak Race in the Village Bay; Chapter Ten The Rolling Competition; Chapter Eleven Re-encounters with the Kayak

Ken Tayor / Cameron

October 26, 2011, revised October 12, 2018

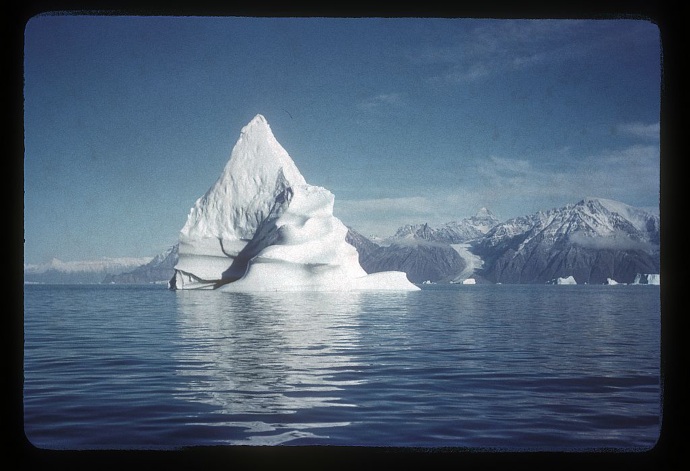

Heading towards the Karrats Isfjord hunting area. The mountainous spine of Karrats Island visible behind the iceberg on the left.

Another nice looking Greenland iceberg.

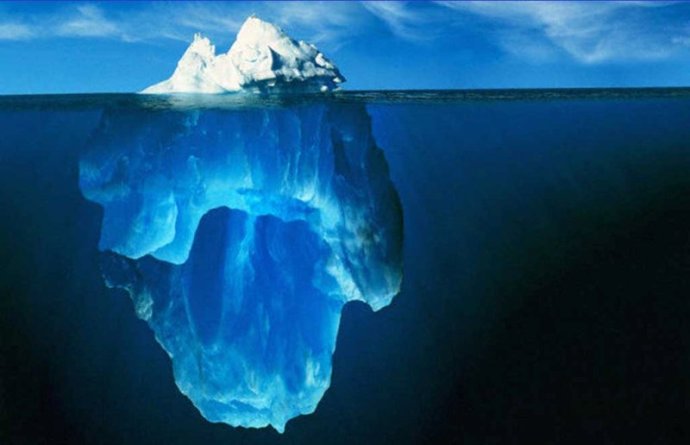

BUT —

this is the complete picture! I found this amazing photo (in the “Life in small bites environmental blog”) and couldn’t resist inserting it here. It’s entirely relevant, of course, as an iceberg rolling over is one of the many life-threatening hazards faced by the kayak hunters.

Introduction

Soon after I arrived at Illorsuit, two weeks went by without anyone in the village catching a single seal. For me that was disappointing, but for the villagers it was really serious, it meant that there was not enough to eat. Besides a few rowing boats and dories, there were three boats with inboard motors in Illorsuit in 1959. Tobias and Edvard Nielsen owned one of these large enough for four people plus kayaks. They and their brother Enoch were already planning a hunting trip of several days to the Karrats Isfjord. They invited me to go along.

The plan was to first camp on Karrats Island and try the hunting there and then carry on to the well-known Umiamako hunting camp. The camp is on a promontory between the Umiamako glacier and the well-known Rinks glacier — which was one of the four most productive on Greenland’s west coast. We would go there because the fresh water melting off the face of the glaciers and the many icebergs supports many species that fish eat. And the fish, of course, attract seal.

A 2008 image from Google Earth showing Karrats Isfjord in detail (though with much, much less ice than in 1959). Karrats is the long, skinny island on the lower left. Nuugaatsiaq village is on the other side of the “log jam” of ice. Umiamako glacier comes down from the top center. The Rinks glacier is almost out of the picture on the top right. And the Umiamako hunting camp is on the promontory between the two glaciers.

Here we are on the way to Karrats. That’s Edvard on the left, Enoch sitting in the middle and Tobias standing behind Enoch. They were good company and it was fun travelling and hunting with them. Edvard a rambunctious youngster but impossible not to like, Enoch, some 30 years old, was the funniest person in the village (and the champion kayak roller), and Tobias, at 37, was always very serious, incredibly patient and reliable. Emanuele had already begun to build my Illorsuit style kayak, but that still had a ways to go so I would be using my Scottish kayak. You can see how the kayaks were held in place just above the level of the gunwales of the boat, resting on temporary spars of wood.

One of the many icebergs we passed — an old one that’s obviously already had its underside eroded by the water currents and has rolled over in order to reach a new position of stability.

And then, while we were only half way across the sound, we already saw a seal. Enoch and Edvard immediately lowered their kayaks to the water and gave chase. While they were stalking the seal, Tobias and I were in the motor boat, circling around some fair distance away. Very quickly they caught up with it and harpooned and secured it.

At last I’d seen a successful seal hunt! Not to mention that at last we had some seal meat to eat. This was a wonderful beginning to our trip. They brought the seal back to the boat on the end of the harpoon line and gave that to me for me to pull the seal up to the surface while we got the two men and their kayaks back on board. Sure enough it had sunk quite far and if not harpooned first there would have been no point in shooting it. In the spring the seal still have a good layer of their winter blubber which will keep a seal floating on the surface. But for many seal this is no longer true in the late summer.

We continued on our way towards Karrats Island, some 17 miles from Illorsuit. On the way Tobias and Edvard went after another two seal but didn’t get them. We had some soup, still on the motor boat, and finally arrived that evening.

As soon as we landed Tobias skinned and butchered that first seal and the four of us gathered around the carcass and ate small pieces of raw liver accompanied by pieces of blubber. Another delicacy they showed me is the eyeball. When you bite into it in your mouth the vitreous fluid tastes very much like raw oyster.

I’ve since learned that raw seal liver is an important source of calories, calcium and iron. The blubber, besides its high energy value, has large amounts of vitamin E, selenium, and other antioxidants. It also has Omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin D which, of course, prevents rickets. Another positive effect of consuming blubber is on record for the Uummannaq District, exactly where Illorsuit is — no deaths due to cardiovascular diseases occurred in the 1970s.

Next he boiled up some meat and blubber and we got down to some serious eating. Of course, I’ve been asked hundreds of times what the seal meat was like. What I usually tell people is that it’s like a very rich and tender beef stew. And that it’s delicious! By the way, you get a clear view in this photo of Tobias’ hunting knife, kept under the thongs on his fore deck while kayaking.

Enoch clowning by sucking into his mouth a piece of small intestine. Behind him you can see the “primus” paraffin stove we had with us and a cooking pot made from a dried milk can.

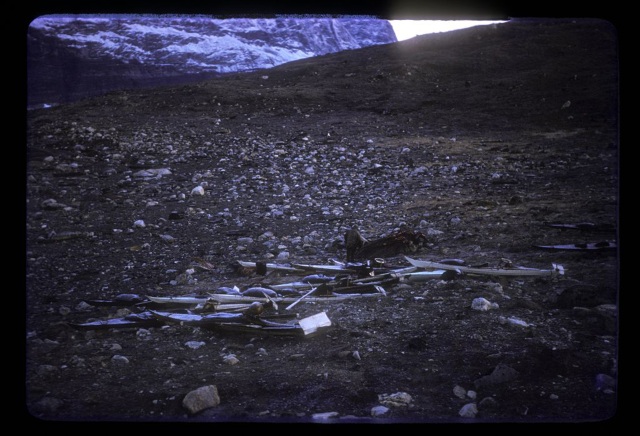

Edvard and I then piled stones over the innards. Enoch tied the seal’s skin and the carcass together and dumped them off shore attached to the boat’s mooring rope. My kayak we took ashore, leaving the others on the boat. All these precautions were because of the dogs that someone from the nearby Nuugaatsiaq village had left on the island for the summer. We had seen them and cursed at them as we approached, but fortunately they never showed up at our campsite. We found a patch of dry ground where we could pitch the tent but it was so rocky that we had to anchor the tent with stones. But there were seal ribs lying everywhere — obviously this was a regularly used hunting camp. We settled down for the night at about 10:00 pm, Enoch and Edvard just lying down on their sides with their hands in their pockets, on the reindeer and dog skin “groundsheet.” Tobias in his winter sleeping bag of dog skin with a seal skin outer layer and I in my down sleeping bag.

Looking towards Umiamako from high on Karrats Island. The photo shows exactly the area where we would soon be hunting.

The next morning we were up at 7:00 for a breakfast of coffee and oatmeal with Tobias and Enoch also eating some more seal meat. There was quite a wind blowing so Tobias and I climbed up the hill to the top of the island to look for any areas of calm water. On the way he spotted a few ptarmigan, in their half brown/half white fall plumage. We got three of them. We climbed higher until we could see a favorable calm patch farther up the Karrats Fjord towards the Rinks glacier. As in this photo, I could see that in the direction of Umiamako the sea was covered with icebergs, brash ice and ice fragments of all shapes and sizes and colors. What you see is the Umiamako glacier, the campsite itself is immediately to the right of it.

We joined the others and decided to go up the Fjord immediately. We had one possible sighting of a seal and then went ashore on the right hand shore of the Fjord. On the way we shot some Ivory Gulls. I stayed at camp that afternoon while the others went out in their kayaks for two hours or more. No seal that time. Tobias had seen five and got a shot at one; Enoch had seen two; and Edvard none.

We spent the night where we were with a brilliant full moon gleaming on the icebergs nearby.

Tobias woke us at 5:30 to a flat calm. We had a quick breakfast of coffee and oatmeal, packed up and set off again back towards Karrats Island. We got a few more Ivory Gulls on the way across but didn’t see any seal. First we landed at the site of the old settlement of Nuliarfik, abandoned in 1934 or 1935 but with still one structure there maintained as a hunting shelter.

A terrible photo! But it’s the only one I have of Nuliarfik. That’s Edvard and me on the beach.

At about 8:30 am we took off again in our kayaks. At last this was my opportunity to accompany one of the hunters in my Scottish kayak to observe and photograph from close up how they went about catching their seal. Tobias and I paddled out into the ice-strewn area between Karrats and Umiamako while the other two kept closer to the mainland.

It’s not so easy to find a seal and I remember long stretches of time slowly paddling along both of us looking to left and right hoping to see a seal among the many, many icebergs and brash ice fragments that seemed to litter the surface of the water. I wondered how is it possible to tell what is a seal and what’s just a piece of dark colored ice or of white ice in shadow. Before too long I realized that what was happening was that we were scanning the water ahead of us as if by radar. You need to scan a wide arc in front of you back and forth, over and over again until: suddenly something has changed. You narrow the arc of your scanning until there it is, there’s what’s different, there’s your seal. Then you wait motionless, ducking down behind your white bow screen and with the advantage of your white camouflage anorak, until it dives again. Next you have to make a judgement as to where it’ll re-surface depending on what species you reckon it is and whether you think that it’s feeding or travelling or sunbathing or whatever else seal do. Tobias seemed to be good at that but several of the seal we saw during those days we never saw again.

Eventually I saw one seal but it disappeared. After sighting another, we were stalking it and were probably getting close when suddenly it surfaced just ahead of Tobias looking in his direction and I thought well, we’ve lost this one for sure. But to my amazement I saw that Tobias was paddling full tilt toward the seal. It reacted by rising higher out of the water as if to get a better look at him. He lifted his harpoon and, by now quite close to the seal, threw it with what looked like all his force. The harpoon hit the seal in the neck and it immediately dived. But the harpoon line was now firmly anchored to the seal and, just as was done in the old days, Tobias had caught the seal using only his harpoon. That was truly extraordinary, something few outsiders have ever seen.

The seal was well harpooned and it wasn’t long before Tobias was able to pull it to the side of his kayak and kill it with his hunting knife. That (what you see in the photo above of three of us eating) was simply what looked like the blade of a pocket knife attached to the end of a two and a half feet long stick that he kept under the deck thongs on the fore deck.

Unfortunately, his catching that seal was one of the times I used the defective movie camera so I didn’t get any photos of that special event. But here, a bit later, is Tobias with the seal attached to the left side of his kayak ready for towing back to camp. The photo shows a lot of the details of his hunting gear. The harpoon line tray with its bone ring to keep the harpoon line in place, with the end of its “pistol grip” leg firmly held in place clipped under a deck thong, its flimsy looking left leg kept in place by the yellow-looking two foot long spar of wood, and its (hidden from view) right leg that ends in a hook for the harpoon shaft, that you can see a piece of, to rest in. Extending forwards from under the line tray is his gun bag — you can see the stocks of his two guns sticking out of it. His fully inflated sealing float on the after deck is the entire skin of a small seal, and the smaller flotation bladder is made of the stomach of a large-sized seal. The forward-pointing bone pin on the strap of the bladder is visible, tucked under the after deck thongs, and also the long spar of wood on the left side of the after deck, where traditionally the killing lance would go. A wind blew up so we headed back, with a great deal of brash ice meaning a lot of twisting and turning to find a way through.

Unfortunately, his catching that seal was one of the times I used the defective movie camera so I didn’t get any photos of that special event. But here, a bit later, is Tobias with the seal attached to the left side of his kayak ready for towing back to camp. The photo shows a lot of the details of his hunting gear. The harpoon line tray with its bone ring to keep the harpoon line in place, with the end of its “pistol grip” leg firmly held in place clipped under a deck thong, its flimsy looking left leg kept in place by the yellow-looking two foot long spar of wood, and its (hidden from view) right leg that ends in a hook for the harpoon shaft, that you can see a piece of, to rest in. Extending forwards from under the line tray is his gun bag — you can see the stocks of his two guns sticking out of it. His fully inflated sealing float on the after deck is the entire skin of a small seal, and the smaller flotation bladder is made of the stomach of a large-sized seal. The forward-pointing bone pin on the strap of the bladder is visible, tucked under the after deck thongs, and also the long spar of wood on the left side of the after deck, where traditionally the killing lance would go. A wind blew up so we headed back, with a great deal of brash ice meaning a lot of twisting and turning to find a way through.

Returning to camp with the seal. This photo gives some idea of how much ice we were surrounded by. Those mountains in the background form the spine of Karrats Island. Nuliarfik was at the near (left) end of the island and our first camp was on the other side and half way down the length of the island. Edvard had got back to Nuliarfik ahead of us but with no seal. We made some soup and then Enoch arrived with another seal. We moved back to our first campsite at the other end of the island where we cut open Tobias’ seal and had the usual snack of raw titbits. This time I fried some liver and all three of us enjoyed it that way. Later on Tobias and Enoch went out again, Tobias saw one and shot it but it got away. Enoch didn’t see any.

Returning to camp with the seal. This photo gives some idea of how much ice we were surrounded by. Those mountains in the background form the spine of Karrats Island. Nuliarfik was at the near (left) end of the island and our first camp was on the other side and half way down the length of the island. Edvard had got back to Nuliarfik ahead of us but with no seal. We made some soup and then Enoch arrived with another seal. We moved back to our first campsite at the other end of the island where we cut open Tobias’ seal and had the usual snack of raw titbits. This time I fried some liver and all three of us enjoyed it that way. Later on Tobias and Enoch went out again, Tobias saw one and shot it but it got away. Enoch didn’t see any.

Tobias skinning one of the seal we caught while camped on Karrats Island. These skins are valuable items. A skin can be sold to the Royal Danish Trade Department store in the village for cash or, depending which species it is, used for clothing, kayak skins, boot soles, harpoon lines, kayak deck thongs, dog whips, sled dog traces, etc.

You can see that two of the kayaks have been taken ashore. Edvard’s and my kayak are the two on the boat. Just in front of the tiller you can see one of the temporary cross spars used to support the kayaks, with my kayak resting on it and the boat’s gunwale. One seal is tied to the side of the boat to keep it “refrigerated” in the cold water, with the towing strap bladder float still attached.

A domestic scene one morning still at the Karrats campsite with Tobias working on the inboard motor, Enoch picking dry grass for lining his kamit or sealskin boots. These have an outer boot with its sole made of the same tough skin used for kayaks and an inner one with the hair left on in the inside. The grass goes between the soles of the inner and the outer. The result is an extremely comfortable, tough, and waterproof boot. It looks like Edvard is cleaning a cooking pot. To the left of him you can see the carcass of a seal. My tubby Scottish kayak in the foreground and Tobias’ behind it with the wooden spar he kept on his after deck. I was told it was there to help steady any small seal Tobias might carry home on his after deck. Much easier, of course, than towing it through the water.

Tobias and Enoch, again at the Karrats campsite, standing beside their kayaks. Enoch is wearing his sealskin trousers and they both are wearing sealskin boots. Again you can see the wooden spar Tobias has on his after deck. His towing strap bladder is still inflated from his most recent catching of a seal. You can make out the keel skeg on Enoch’s kayak, held in place by cords or thongs attached to a slat of wood resting on the after deck.

Whenever I look at this image I’m reminded of Drever’s comment that:

“The Greenland kayak, although very manoeuvable and efficient,

is at the same time so absurdly small and frail …”

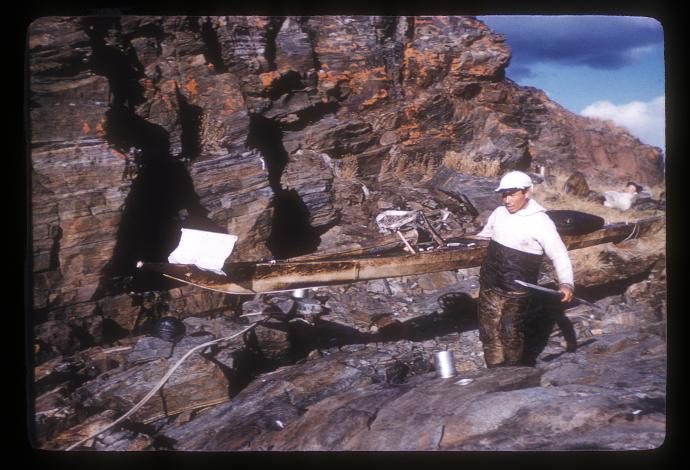

Enoch with his kayak readied for hunting carrying it down to the water. He’s doing so in typical Uummannaq Bay style, the kayak upright, his right arm under the masik (thigh bar) with his thumb hooked over the “knee bar.” You can see his gun bag on the fore deck, under the harpoon line tray, and the skeg in place near the stern of his kayak. In this case he has his white screen already in place at the bow.

His paddle is well out at right angles to act as a stabilizer while he squeezes himself into his kayak (I read somewhere recently that it’s really more like pulling on a pair of trousers). He seems to be simply holding his paddle together with the deck thongs. Given the slight angle on each side of the fore deck the far blade of his paddle could be three inches or so below the surface of the water, enough to resist the kayak leaning in either direction. You can clearly see that he has his harpoon hanging in the water, kept from drifting away in this case by the harpoon line itself. The cold water will tighten up the seal skin thongs that hold its various parts together. As soon as he is ready to take off he’ll settle the harpoon in its regular place, on his right, beside and in front of him on the fore deck. You can also see the “wings” at the back end of his unusual harpoon with his throwing stick in place immediately in front of them. The harpoon is pointing “backwards,” of course.

His paddle is well out at right angles to act as a stabilizer while he squeezes himself into his kayak (I read somewhere recently that it’s really more like pulling on a pair of trousers). He seems to be simply holding his paddle together with the deck thongs. Given the slight angle on each side of the fore deck the far blade of his paddle could be three inches or so below the surface of the water, enough to resist the kayak leaning in either direction. You can clearly see that he has his harpoon hanging in the water, kept from drifting away in this case by the harpoon line itself. The cold water will tighten up the seal skin thongs that hold its various parts together. As soon as he is ready to take off he’ll settle the harpoon in its regular place, on his right, beside and in front of him on the fore deck. You can also see the “wings” at the back end of his unusual harpoon with his throwing stick in place immediately in front of them. The harpoon is pointing “backwards,” of course.

The next morning we woke late at 7:30 or 8:00. Enoch went up the hill and said no wind in the direction of Nuugaatsiaq. This is the most northerly village in the Uummannaq Bay, located on a fairly large island northwest of Karrats Island and some 25 miles north-northeast of Illorsuit. So it was only some six or seven miles from our camp. We had a quick breakfast of oatmeal and set off.

Approaching Nuugaatsiaq. About half again as big as Illorsuit and maybe a little less well off. Of course, the brothers knew people there and were glad to be able to visit. We got another Ivory Gull but saw no seal on the way to the village. We did some shopping in the store (I was able to buy a kayak coaming ring, at last!) and the Outpost Manager invited me for lunch. Two young boys tried out my kayak and I noticed that there seemed to be very few kayaks in the village. Later I joined Tobias for coffee in the house of a special friend of his where they had a photo of him and his wife and one of Anna and Johan Zeeb, of Illorsuit.

A view across the village. As is typical, the larger houses with pitched roofs are those of the Trade Department — the manager’s house, the store, warehouses, etc.

Our boat with our four kayaks on board moored by the village pier. That’s the south end of Karrats Island showing on the left. And in the distance that’s Ubekendt Island so here we’re looking straight towards Illorsuit!

One of the village boys trying out my kayak. This shows a bit more clearly how our kayaks were loaded onto the motor boat.

Some of the Nuugaatsiaq boys and to show how much ice there is outside that village.

Soon we took off again, heading up the ice-filled Sound toward Umiamako. It looked to me like a “dead” glacier but they said it still produced a few icebergs. Beyond the promontory where we planned to camp was the Rinks Glacier, the source of the huge quantities of ice surrounding us on all sides. It was a bit too windy for any hunting and in any case we saw no seal on the way.

And, finally, we were approaching the hunting camp at Umiamako. It had been obvious at Nuugaatsiaq that most of the kayakers were away from the village. Somehow, no-one mentioned to me that they had (also) gone to Umiamako. So, for me, it was a wonderful surprise when we got there to find the beach already occupied by a number of kayaks and two or more carcasses of butchered seal.

Two views of all the kayaks.

Umiamako, even more so than where we had camped on Karrats Island, was truly a traditional hunting site as the beach was littered, almost made of seal bones from years of successful hunting. As we approached two of the Nuugaatsiaq hunters were returning to camp, but without any seal. Altogether there were twelve of them at the camp. We joined them at their dwarf willow campfire and also got Tobias’ primus stove going. We all ate seal meat (first some of theirs and then some of ours) ‘til we had room for no more! Then we had coffee in our tent. The Nuugaatsiaq men had only one smaller tent of their own so some of them slept with us in ours, everyone using everyone else’s bodies as pillows. Again it was only Tobias and I who had sleeping bags. But Bent Jensen had told me that the Inuit always said that they had more colorful dreams if they were cold while they slept.

Early the next day, Edvard and Tobias in front of some blue ice.

As you can see, the weather was overcast most of the time while we were at Umiamako and by afternoon it was generally too dark for photography. So it was only in the mornings, in my Scottish kayak, that I went out with Tobias to photograph his hunting. In the afternoons I had the opportunity to watch and photograph all the hunters as they left for the second hunt of the day.

As I’ve said, Tobias’ catching that seal without needing to use either shotgun or rifle was a quite exceptional piece of luck. So I was very aware that what I would see now would be the more typical 1959 style of seal hunting, using firearms. Given that a dead seal might easily sink (like the one they caught on our way from Illorsuit to the Karrats campsite), however, harpooning the seal was still an essential feature of the hunt.

That morning at 6:30 or so, after some tea and hard tack, it seemed that everyone at Umiamako launched their kayaks and set off in search of seal. Surprisingly soon I saw one but didn’t yet have my gun at the ready so couldn’t get a shot at it. We paddled after it, joined by two of the Nuugaatsiaq men. As the seal got farther away Tobias dropped out and I kept on with the others until finally it disappeared.

Later Tobias told me any number of men can chase a seal, it’s all to the good. He and I paddled towards a large iceberg and I had the strongest feeling that we were about to see a seal. I told myself to calm down and then suddenly saw one away off to the right. Tobias was already chasing another seal so I had the chance of going for it myself. I judged its dive well and was close enough to shoot but at best I wounded it only slightly. It came up again on the left and again two or three more times but never close enough for another shot. Tobias joined me and he got a shot at it but then it disappeared. Almost immediately I saw another one, or maybe the same one, far ahead. It surfaced once more and then disappeared. There was thick low cloud blowing in now from out to sea so we headed back to camp. We met up with Edvard who had no seal but had seen 10! I then saw one and Tobias got a shot at it and then shot it a second time. It then resurfaced far away but when we went after it I got close enough to shoot it. For a while we seemed to have lost it then it surfaced twice close by and then again far off to our right. Tobias and I went after it and he shot it for what was a fourth time! At last he got close enough to harpoon it. He killed it with his .22 and soon had it attached to the left side of his kayak and was towing it in to camp. But catching that seal had taken us all of an hour from first sighting to when he was finally able to kill it.

This seal resurfaced almost beside Edvard’s kayak and here he is trying to harpoon it at very short range.

It began to snow as we approached the campsite as happened again two or three times during our trip. We left the seal tied to the mooring line and came ashore. Two seal had been caught by Nuugaatsiaq hunters, one was cut up already, the other was brought in just as we arrived. We piled into the tent for some fried liver and soup. Another hunter was seen returning with one and it was a Harp Seal! I arranged to buy the skin for my kayak, and I knew there was another skin at Nuugaatsiaq I should be able to buy. Enoch said that he’d also seen a Harp Seal earlier that day.

At 3:15 the snow stopped and the sun tried to come out with the sea as flat calm as ever. Immediately four or five hunters took off and Tobias and Edvard went off together. First back was young Edvard towing two seal! That was a really big success for him. Then one of the Nuugaatsiaq hunters came in, also with two seal. Tobias got back with one. Four other seal were caught by Nuugaatsiaq hunters for a total of nine seal that afternoon, 13 altogether that day. Most of them, of course, were Ringed Seal but at least one was a Harbor Seal and one was the Harp Seal I just mentioned.

By 1959 there had been a number of innovations in the techniques and equipment for seal hunting by kayak. These were all related to the introduction of firearms, both shotguns and rifles. In the days before firearms, the hunters could use the waves to hide themselves from the seal in order to get within harpooning range. In fact, Otto Fabricius says that in his day (1768-73) the hunters would use one or the other technique — using their firearms only in calm weather! But by 1959, at Illorsuit, kayak hunting was always done using the guns.

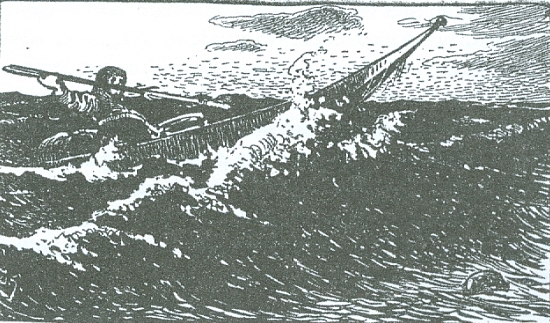

Image from Qajaq vol 3, no. 1-2, 2005, page 30. copyright QajaqUSA.

This shows the way in which a hunter might use the waves themselves to hide behind in approaching his prey. In this case he seems to be using a bird dart, not a harpoon, so that must be a bird on the surface of the water.

The most obvious of these innovations was, of course, the gun bag, made of seal skin. It was added to the equipment on the fore deck, its front end attached to either the bow deck thong or a special skin piece sewn onto the deck, its rear (open) end attached to an appropriate fore deck thong. In the Uummannaq Bay district a hunter kept both his shotgun and his rifle in this gun bag. The keel skeg was also related to the use of guns as it improved the directional stability of the kayak, important for safe and accurate shooting. Hunting in calm weather with no waves to hide behind, the white camouflage bow screen was introduced. While hunting it was in place near the bow and otherwise rolled up and tucked under the deck thongs on the left fore deck. By crouching down behind this screen, the hunter could hope to look like a piece of floating ice. Typically the hunters also wore thin white anoraks over their other clothing and sometimes a white topped hat. Also for camouflage, the one canvas kayak at Illorsuit was painted white as were seven of the 17 sealskin kayaks. By 1959, because the use of firearms meant hunting only in calm weather, hunters wore only the spray skirt or waistband (tuitoq). The full-body tuvilik was used only for learning and practicing kayak rolling.

First, of course, would be the search for a seal and then the stalking of any seal discovered. If the stalking went well and the hunter was able to come close enough to the seal, he would then attempt to wound it with his shotgun. This could be done from farther away than it was possible to throw a harpoon. Once it was wounded the hunter could usually, but not always, approach the seal to within harpooning range.

This shows Tobias as he fired at a seal with his shotgun. His sealing float is still on the after deck of his kayak which let’s you know that’s what he’s doing and that he hasn’t yet harpooned the seal.

This is a seal we were hunting, already wounded and harpooned.

Tobias posing in the harpooning position. His hunting float is already gone from the after deck, so he’s already harpooned a seal.

Tobias being right-handed, his 7 foot (knob-style) harpoon, with harpoon head in place on the 10 inch ivory fore-shaft was kept ready on the right side deck, pointing astern and with its throwing stick uppermost. It was held in place by a bone hook on one leg of the line tray and a large bone “button” on the edge of the deck beside the front of the manhole. At the moment of harpooning he lifted his paddle clear of the water and raised the harpoon, rotating it to point forwards. Leaning well back he vigorously hurled the harpoon, holding on to the throwing stick which hinged free to act as an extension of his arm, adding considerably to the force and to his control of the flight of the harpoon. When the seal was struck by the harpoon it dived immediately and this movement broke free the fore-shaft, which hinged over on its loop of thong, releasing the harpoon head and allowing the harpoon itself to float clear to be recovered later. The harpoon head, which was small enough that you could have hidden it in your fist, was a sharpened metal point on a toggle shaped bone “body.” Pulled by the drag of the line and float, the toggle-shaped harpoon head will then have swiveled around under the skin of the seal to give a firm anchorage to the 40 foot line with its inflated float. As soon as the harpoon was on its way, Tobias freed up his right hand by quickly taking his throwing stick between his teeth. His harpoon line (made from the skin of a Bearded Seal), had been lying, carefully coiled, on the harpoon line tray above the gun bag on the fore deck. With the line unreeling from the line tray, he grabbed the float on his after deck and pulling it free of the deck thongs he bunted it with his elbow far out to his right. In that way, harpoon, line and float were all well clear of his kayak and there was less danger of his being capsized by the line getting snagged on either the kayak itself or any of the hunting gear on the decks. The float, made of an entire small seal skin, will have greatly impeded the seal’s attempts to escape and was more than buoyant enough to stay on the surface even if the seal, once killed, sank to the end of the line. Once he had it harpooned, Tobias was soon able to kill it and prepare it for towing back to camp.

Here he has a seal safely harpooned, as you can tell by the sealing float being out in the water in front of the kayak. You can see the seal’s head where it has resurfaced right beside the kayak. After harpooning the seal, depending on the circumstances, the hunter would kill it with a shot of his .22 rifle or with his hunting knife. Once, I even saw Tobias pull on the harpoon line, two different times, trying to bring the seal to the surface so that he could shoot it.

Maneuvering his kayak to get in position to take a shot at the seal,

and now he is shooting to kill the seal with his light weight rifle.

That low cloud coming over gave us a brief snow shower. I thought we might lose visibility but on all sides of us the icebergs were still dimly visible so that at no point did we in fact lose our bearings and all was well.

Now that he has the seal caught and killed I’ve paddled close to his kayak and here he’s lifting up the seal to let me get a good look at it.

And now he begins the fairly complicated process of preparing the seal to be towed back to camp.

Making the incision needed to attach the forward towing strap. He has a forward and a rear towing strap both kept inside his kayak. The forward strap is attached under the seal’s chin so that it’ll be on its back when being towed. Half way along the strap is a bone “button” which he’ll tuck under one of the fore deck thongs. There is also a toggle like handle, or sometimes just a loop, at the end of the strap.

Inflating the small flotation bladder which is part of the rear towing strap. This strap will be attached to the after deck thongs with the longer bone pin you can see, pointing forwards.

Making an incision in the skin of the seal’s belly where he’ll attach the rear towing strap.

And with that now attached to the seal, he’s ready to bring it round to the left side of his kayak. At this point he has removed the harpoon head from the seal. That’s it just below his left hand.

Making adjustments. You can also see his paddle in place as a stabilizer.

The seal floating free as Tobias re-arranges all his hunting gear before putting the seal on the left side of his kayak. He re-coiled his harpoon line, set it just the way he likes it on the line tray, armed the harpoon with its toggle head, put the harpoon back in place on the deck beside him, his knife back in place on the fore deck and the hunting float on the after deck. With that all done he paddled over to the seal and used the towing straps to attach it firmly against the left side of his kayak.

Which is what this photo shows (from an earlier hunt). He’s decided to return to camp. With his white screen removed from the bow, he’s not expecting to see and hunt another seal. However, if another seal appears and he decides to go after it, all he has to do is give a quick pull on the end of the forward strap which releases it from the kayak. The drag of the seal’s body in the water will then pull the rear towing strap free of the after deck thongs and the seal will float clear. The bladder float serves both as flotation should the seal be especially lean and likely to sink and as a marker to help the hunter find that seal again when ready to do so. When a hunter catches two or more seal these are towed one behind the other and can be released with that one single pull.

At Umiamako, three of the Nuugaatsiaq hunters getting their kayaks down to the water for the afternoon hunt.

Another hunter about to take off.

And, ready to leave. The hunters usually did so two or three of them together but typically they would soon separate and each go his own way. In their 1963 report the Cambridge students tell of how “when two hunters … perhaps never come within two miles of each other … such pairs used a simple system of calls to maintain contact, thus hunting more effectively and with greater safety” (1963, page 4).

A closer shot of three of the butchered carcasses on the beach.

Myself, doing something or other to my kayak.

Tobias, readying his kayak, deflating his flotation bladder after a successful hunt.

Tobias, readying his kayak, deflating his flotation bladder after a successful hunt.

You can see five of the Nuugaatsiaq kayaks have been painted white for camouflage. Some of those may have been canvas covered but I don’t think so (see more in Chapter Six “Skinning the Kayaks”). Also that two of these white kayaks have a spar of wood on the left after deck, just as Tobias’ has. Almost a close-up, too, of how the skegs are attached to the kayaks in these villages, with cord or thong to a small wooden cross piece on the after deck. Notice how all the kayaks have been set down on the rocks so that the stern skeg is in mid-air in no danger of being knocked out of correct position.

One of the Nuugaatsiaq hunters on the last morning at Umiamako. Karrats Island in the distance, behind the sunlit iceberg.

One of the Nuugaatsiaq hunters on the last morning at Umiamako. Karrats Island in the distance, behind the sunlit iceberg.

The next morning it was too windy so we decided to head for Nuugaatsiaq and then reconsider the weather conditions. If not good enough we would just carry on home to Illorsuit. Three of the Nuugaatsiaq men joined us on the boat so we could tow their kayaks. To keep their kayaks dry, they tightly tied the top of their tuitoq around their throwing sticks put vertically in the middle of the manholes. This time Tobias and Enoch had their kayaks tied on under the cross spars to stop heavy seas coming into the boat. As we approached the village we shot some duck but we didn’t see any seal. Some more shopping, including that other Harp Seal skin and we then headed south past Karrats Island until close under the cliffs of Upernavik Island, across the sound from Illorsuit. On the way, Enoch put out a fishing line and very quickly caught a number of small cod which we cooked up right away and made a large meal of. That seemed better than eating any more of the precious seal meat. And then across the sound to Illorsuit.

It was dark by the time we got back but there was a welcoming party waiting for us at Enoch’s house. Before long, we unloaded the kayaks and got them onto their racks. We left the seal meat and game birds to be sorted out next morning and I went to bed euphoric after what had been for me some of the best days of my life.

Upernavik Island at sunset. Where we stopped and ate the cod.

We had spent two nights on Karrats Island, one night farther up the Rinks Fjord, two nights at Umiamako and altogether we were away from Illorsuit for six days. During that time, Tobias and his two brothers caught nine Ringed Seal, while 26 others (at least one of them a Harp Seal) were seen but escaped. I had watched and photographed Tobias successfully hunting four seal and stalking another six that got away. While we were with them at Umiamako, the Nuugaatsiaq hunters caught at least nine (one of them a Harp Seal and one of them a Harbor Seal).

Lots of visitors to my tent in the morning, some with the paddles and harpoons for my and John Heath’s kayaks and the tuitoq for mine. That was fun and I enjoyed thanking them all, paying them for what they had made, and admiring their craftsmanship. Then I went along with Enoch to the motor boat which was moored opposite Tobias’ house and we all got our things sorted out. We agreed that Tobias’ wife Emilia would prepare the Harp Seal skins for my kayak. I got some of the seal meat and the several birds I had shot on the trip.

Soon my tent was again full of happy visitors and we spent the rest of the day eating meat, drinking coffee and beer, laughing and telling stories about the places where we camped, about meeting the hunters from Nuugaatsiaq, the ice, the snow, and the many seal that we had seen and hunted.

Another look at Tobias towing that seal he caught by harpoon only, without use of either of his guns.

- – x – x –